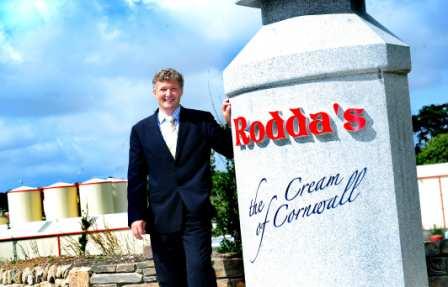

With the growing reputation of Cornish produce, a select handful of Cornish brands have established themselves a reputation and recognition that extends well beyond the Tamar. When people up country think of pasties, they think of Ginsters, ice cream its Kellys. And with clotted cream, Rodda’s instantly springs mind.

MD Nicholas Rodda is the fifth generation Rodda to run the business, and is fiercely proud of the legacy that has been built up in the Redruth-based family firm over the past 120 years. He outlines his vision for Rodda’s future, how the business is expanding beyond clotted cream, and why it does actually make sense to deliver to a supermarket down the road via Bristol.

Business Cornwall: Rodda’s has a long-established reputation. How has it developed over the years?

Nicholas Rodda: Yes, fifth generation, founded in 1890 by my great great grandfather and we’re still on the same site.

Over the years we have grown organically, but because we have been on the same site and built bits onto the factory, it didn’t always keep up with the modern regulations.

So about seven years ago we took the decision, with help from Objective One, to redevelop the whole factory. Basically we built a whole new factory over the top of the old one. And we had to do that while we were still operating. We had partitions up. During the day we would produce the cream, and during the night builders would move in and knock down walls etc.

BC: Not ideal!

NR: No, but we demonstrated we had good control, good seals. Everything had a deep clean every morning, so health and safety wasn’t compromised.

BC: Was working around it the only option?

NR: It was. It’s not like an ice cream manufacturer that could produce three months of stock and then shut down, we produce something every day of the week to meet customer orders.

The work went on for about 18 months in total. It was a fraught and stressful time, but we managed to maintain the same rate of production to meet customers’ demands.

BC: Have you always been involved in the family business?

NR: I have and I haven’t. I went to Cornwall College and did business studies, and I was going to go away to university to study accountancy. In the summer I came here to work, in the production area. But then one of van drivers unfortunately had an accident and was out for the rest of the summer, so I was pushed out onto the van. I got used to earning a little bit of money.

And I thought if I go to university, I don’t know what that is going to teach me, I would probably learn more here hands on, so I stayed and ended up working throughout the whole factory. I have probably done every single job there is to do.

BC: How long have you been MD?

NR: About four years, but I’ve been working here since the 1980s. I took over as MD from my father.

BC: Is the company still wholly-owned by the family?

NR: It is. There are three generations that own the business. There’s my grandfather’s brother, Eric Rodda. He’s about 95 now but still keeps a keen active interest in the business. I meet with him regularly to tell him what’s happening and we have a shareholders’ meeting and he comes in and has some fantastic questions.

And then on my father’s generation, there are four directors and three of those have retired now. Currently running the business are myself, my brother Andrew, he’s operations director; finance director Kurt Sigrist, who is the first non-family member to come in; and Philip Rodda is the chairman.

BC: It’s quite unusual for such an established company to be still owned by the family.

NR: Everyone keeps saying to me, in a family business it’s usually the third generation that wastes it and makes it bankrupt, but we’re on the fifth generation now.

BC: Was there ever any pressure or obligation on you to join the family business?

NR: There was never any pressure as such. When you’re younger you don’t necessarily know what you want to do in life.

Growing up, you think you’d like to work in the family business, and then maybe move on and gain some experience elsewhere. But there was never any family pressure.

BC: But what about from yourself, a feeling of duty perhaps to uphold the traditions?

NR: There probably was once I had started in the business, I felt I probably couldn’t leave. But I think it is a tremendous privilege to be a fifth generation of the family to run the business and have the trust of the family members to do so.

BC: Going forward, are there more Roddas ready to carry it on?

NR: There are. Some are off doing other careers, but still interested in the business. It’s a very hands on sort of business and very demanding on your time and hard work. So I’d like to think if someone from the family did come, they would not come in with rose coloured spectacles, thinking it would be an easy ride.

BC: Like you, they would start at the bottom and work up?

NR: Definitely. I think you have to go through the business and have a good understanding of everything it does. How can you tell somebody what to do, if you don’t know how to do it yourself? For years I used to go out and do deliveries, worked in production and so on. There’s nothing really that I wouldn’t be able to roll my sleeves up and get on and do.

BC: And that must help gain respect.

NR: I think some people think that running a business is quite easy. But we’ve got a number of people who have been here a long time, and remember when I used to work on the vans. So they think ‘he’s done, what I do’, so there is an empathy. You can speak to them with a qualified knowledge.

BC: Would the family ever consider selling the business? It’s a question you must get asked a lot.

NR: (laughs) We’ve never really been approached by a big company wanting to buy the business. I don’t know if it’s because your name is on the door and they assume you wouldn’t be interested. But I would like to think that I would never be forced to sell it, through a family problem or market condition or whatever.

BC: What if someone came through the door and made you an offer you just couldn’t refuse?

NR: I don’t think money is everything. You’ve got to be happy. If you sell, once you get over the initial excitement and been paid some money, you’ve still got to go out to work and do something.

My view is that it’s been passed on you, you have to make the best of it and try to pass it on in a better state than you received it. So I would like to think it would go on for another generation.

BC: I guess Rodda’s is a valuable brand name?

NR: Probably being a bit modest, we don’t think of Rodda’s like that. People say we’re famous, I don’t know about that. I think we’ve got a good name in clotted cream and dairy products because we’ve been going for such a long time. We’ve built our brand up on quality and service and have tried not to let anybody down.

BC: But it has national recognition.

NR: Yes, we supply across the country, we’re in the multiples, do a little bit of export to Hong Kong and Japan, Holland as well. It’s only a small part of the business, but nevertheless it’s still a fantastic thought to think someone is actually having a cream tea in a hotel in Hong Kong that originated from Cornwall. It’s not only good for Rodda’s, but it’s good for Cornwall as well.

BC: Cornish Clotted Cream has a geographic protected status now, when did that come in?

NR: It was probably 1993, 94 when they first began the process. It was my father and directors of the time who thought they would like to protect Cornish Clotted Cream, not just for Rodda’s but also for Cornwall.

BC: Were there many other people doing clotted cream outside Cornwall?

NR: There were two or three, but the main motivator was as with what has happened to the Cornish Pasty, where a big multinational gets hold of a fantastic product and reduces the quality right down to a poor imitation. From Cornwall’s point of view, if you’re going to put ‘Cornish’ on it, it should be made in Cornwall with Cornish products and made to a traditional process.

The registration process took about five years, and because they were one of the first to do it, it was ground breaking territory and they had to jump through all the hoops, and we finally gained the accreditation in 1998.

BC: And has it had a positive effect on business?

NR: It has, but the problem we’re up against is that the general public aren’t really that aware of it. People have become more aware of local food and provenance, but it’s actually getting the knowledge out there about what this European mark actually means.

It’s good for Cornwall to have a product which has a protected status, but it’s also a guarantee for the consumer when they go in and buy a tub of Rodda’s Clotted Cream, they know that it has been made in Cornwall to a traditional process.

BC: The Cornish Pasty is coming towards the end of this process, do you think there will be a similar effect there if it’s granted?

NR: Hopefully it will. People say it makes no difference if you put a place name on it, but if it doesn’t make any difference to the manufacturer, why bother putting Cornwall or Yorkshire on it in the first place. There is a distinct marketing advantage, and I think Cornwall should be seen a home for good quality products and not just capitalising upon the good countryside.

BC: What is so special then about Cornish Clotted Cream, opposed to others?

NR: (laughs) Now you’re getting into a sticky areas with Devon and Cornwall which we probably won’t get into. We have our own producer group, so all the milk comes from Cornwall, the majority from a 30 mile radius of our factory in Redruth, Lizard, Land’s End and Truro areas. The milk comes in overnight and is processed the next day. The quality of the milk we get in is very creamy with a lovely golden colour to it.

BC: You must have a close relationship with your suppliers?

NR: They’re a very important part of the process. Without good milk, we wouldn’t be able to produce good quality clotted cream and they get paid a bonus for supplying us over and above. There’s a three-way contract, between Milk Link, so they’ve got the security of belonging to a larger cooperative, then they get a bonus payment for supplying us as well. I think there’s also a sense of pride for the farmer. They can go into Sainsbury’s and say ‘that was my milk that made that cream’.

BC: Do you sell the milk at all?

NR: Clotted cream has been our main line for a number of years, but we’ve also just started bottling milk. It may seem strange that we’ve been going for 120 years and haven’t bottled any milk. We only launched it in March, we realised people in Cornwall wanted good quality milk, we have fantastic milk so we just started bottling it.

BC: Do you make any other dairy products?

NR: We do a little bit of butter and some crème fraiche as well, but clotted cream is still our main line and is probably about 95% of our business. There are some advantages in that. My grandfather used to say if you don’t make clotted cream well, you won’t eat. So there was always a particular focus on that, trying to do it really well. But with resurgence in local produce and coupled with our development which has enabled us to make these products here, we are looking to expand into some other product lines.

BC: Can you say what exactly?

NR: It’s probably a bit of a secret at the moment!

BC: How are you relationships with the big supermarkets?

NR: The majority of the food is brought through the national retailers. I think we’ve got a good working relationship with them, but they’re tough, they’re demanding and have every increasing standards for hygiene and factory standards.

Also there’s a demanding delivery regime. For instance we might get an order for clotted cream on the Monday morning, and it needs to be in Doncaster by Tuesday morning. We have to make everything in advance, because making clotted cream is a two-day process. Lorries are going out every day, but we do some joint distribution with Ginsters.

BC: There was some hoo-hah in the press recently about that, and lorries travelling hundreds of miles just to deliver next door?

NR: It seems crazy from the outside, when Tesco is two miles from the factory. We could deliver direct to them, but there are 14 other Tesco stores in Cornwall, then Devon and Somerset. You would actually need a lot more vehicles. And if every supplier did that, there would be chaos, although it does seem odd that something goes from Cornwall to Bristol and back to Cornwall again. But logistically speaking, it does reduce vehicle movements overall.

BC: The business has grown, but have processes changed much over the years?

NR: The actual process of making clotted cream hasn’t changed that much. We always ask ourselves, if we make a change, what benefit will that be to the clotted cream? The process is quite simple, there isn’t a lot to change, and there are no ingredients – just Cornish milk. But over the years, we have found some other uses for our milk. For every 100 gallons of milk we get, you only get six gallons of cream and 94 gallons of skimmed milk, which is our waste by-product.

BC: So previously that was tipped away?

NR: Years and years ago, nobody wanted to drink skimmed milk so it was tipped down the drain. We had a farm then where we used to have turkeys, and they were fed this skimmed milk in with their feed because it was cheaper than water. Why give them water when you are throwing away skimmed milk? But now there is a commercial value to it, you couldn’t afford just to throw it away. So now on some days, we have eight artic lorry loads a day go out of here with skimmed milk, which will either go to food manufacturing as an ingredient, or will be dried for power, which will then be used for food manufacturing.

BC: Do you see clotted cream as more of a gift item than an everyday purchase?

NR: I think people in the west country tend to eat it on more of a regular basis, but up country we’ve done some research that people buy it maybe three or four times a year for a special occasion. But it is becoming more popular.

BC: So demand for clotted cream is generally rising?

NR: Demand has gone up, especially since we’ve started exporting to new markets. We’ve also seen an extension to its the shelf life, which has helped. When we started cream would keep 2-3 days, now it’s 12-14 days, but much of that is down the technology of the fridges. But is has given people the confidence to use it in their tea rooms and hotels.

BC: The leisure industry must be big part of the business?

NR: Very much so. We have a fleet of vehicles delivering to shops, restaurants and hotels, and as you get the influx of holiday tourists, demand goes up. But we’re also trying to promote it to tourist areas outside the county as well. So when you go to the Lake District, for instance, you can get a cream tea there as well, but rather than have it with the squirty cream, shaving foam as I call it, you should be able to have Cornish Clotted Cream as well, so you’re getting the real deal.

BC: How much cream do you produce in an average year?

NR: We don’t tend to think about how much we produce in a year, we’re not a huge figures-driven business. Our production varies, there are peaks and troughs. In January we could produce five or six tons in a day, while leading up to Christmas we could produce 25 tons in a day. As we’re going through the seasons, Easter will be a kick for us, and then we really start to get busy when the soft fruits come into the shops around the Wimbledon time.

BC: The business must have quite an effect on the local economy.

NR: We’ve never really thought about it, but someone did say to us we’re probably employing the size of a small village. We employ 140 people directly here, but within our supplier producer group we have about 150 farms.

BC: Has the economy impacted on the business? It must be seen as a luxury product.

NR: Clotted cream is definitely something you could live without, but I think we have seen a slight shift, where people eating out in restaurants has decreased, but there has been an increase in people going into shops and supermarkets and having clotted cream at home.

This article appears in the November 2010 issue of Business Cornwall magazine